Democratic Senator Kay Hagan recently lost her bid for reelection in North Carolina to Republican Thom Tillis. Careful analysis strongly suggests that Hagan and her team should not have shied away from Obama in her 2014 campaign. Obama’s participation could have helped activate the state’s disinterested Democratic and African-American bases the way he did in 2008 and 2012.

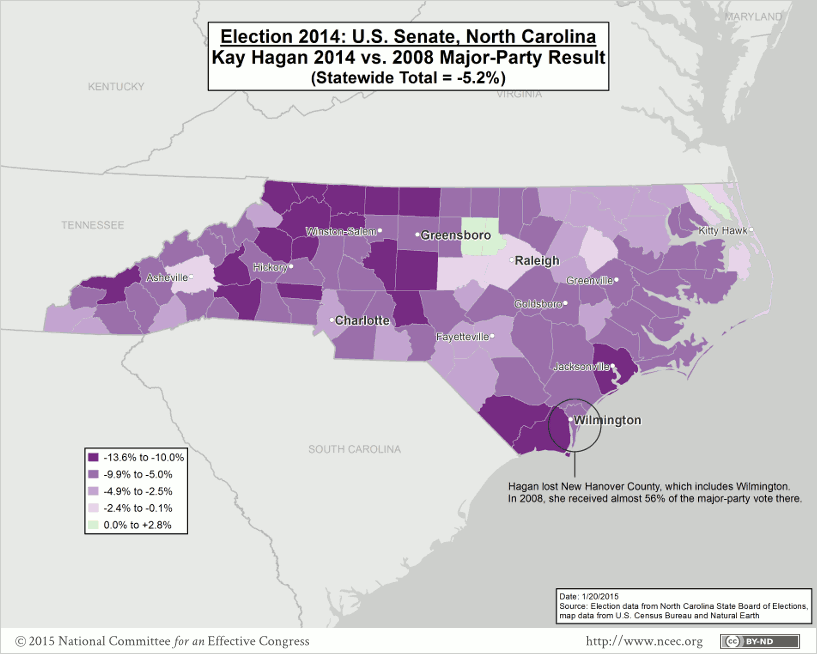

While data analysis helped predict which populations would reliably turn out for Hagan, Democrats did not take into account the degree to which the data from 2008 (the last time Hagan was on the ballot) was influenced by President Obama’s first campaign.

Kay Hagan lost by 45,608 votes (approximately 2 percent of the vote) in North Carolina,where 44 percent of the registered voters cast ballots in 2014. This defeat was not a total shock, but polls such as Real Clear Politics did show Hagan having a slight lead over Tillis up through Election Day. Also, Hagan won among early voters with 601,891 votes (53 percent), which is typical for Democrats in North Carolina, but lost the in-person vote on Election Day.

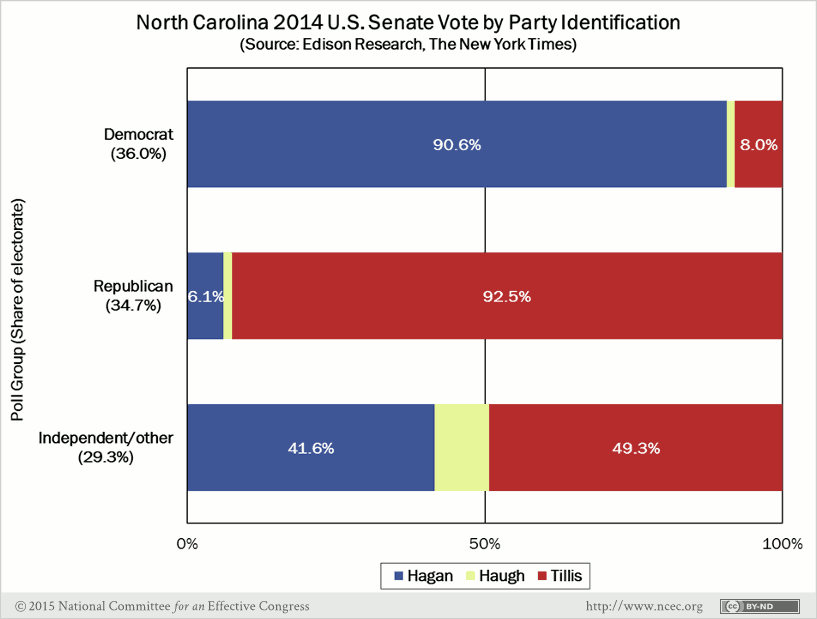

Party

The last Democrat to run for senate in 2010 was Elaine Marshall. Marshall lost the election by 312,972 votes (12 percent of the vote); however, she was running against the popular Republican incumbent Richard Burr. Hagan, in 2014, outperformed Marshall, in 2010 (49 to 44 major-party percent); but Hagan had the name recognition and incumbency that Marshall lacked.

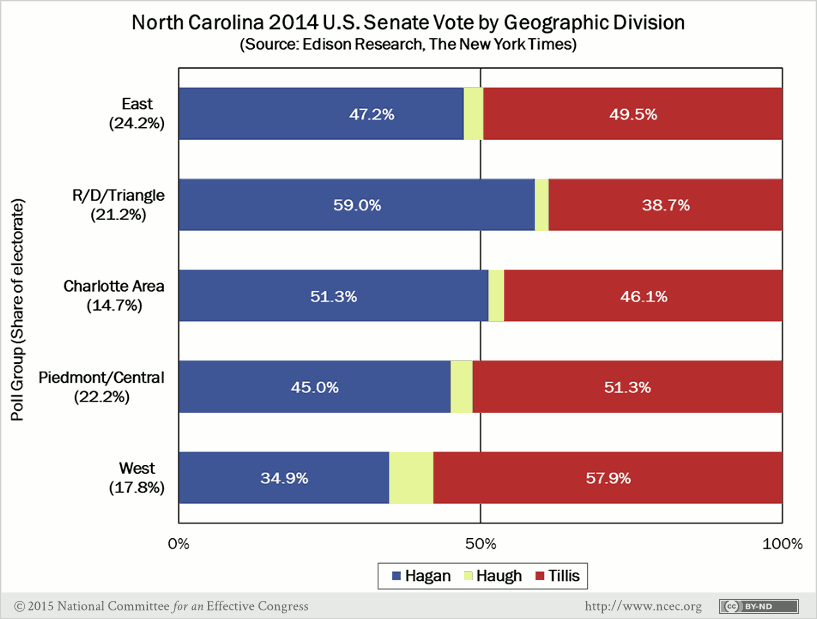

While early voting results encouraged Democratic overconfidence in Hagan’s race, Libertarian Sean Haugh also caused problems. Pre-election polls overestimated how many votes Haugh would draw away from Tillis, as North Carolina’s conservative population is less radical than the Libertarian party line. As such, the Hagan camp thought that Tillis would have to fight a two-front war when Haugh was not actually a major contender.

It is important to note that between Hagan’s last election and this one, far fewer Democrats came out to the polls. Republican leadership, on the other hand, succeeded in engaging their voting base. From 2008 to 2014, according to voter self-identification, Democratic affiliation dropped from 42 to 36 percent, Republican affiliation rose from 31 to 35 percent, and Independent affiliation rose from 27 to 29 percent. Among self-identified Democratic voters, Hagan had the same performance in 2008 as she did in 2014—90 percent—and she saw an almost 3 percent increase in Independent support, but lost 4 percent of support from self-identified Republican voters.

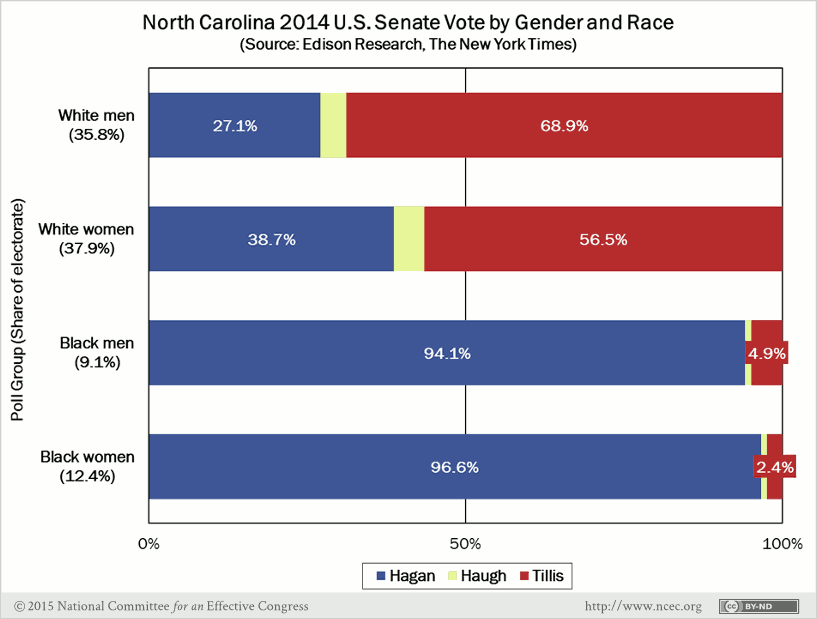

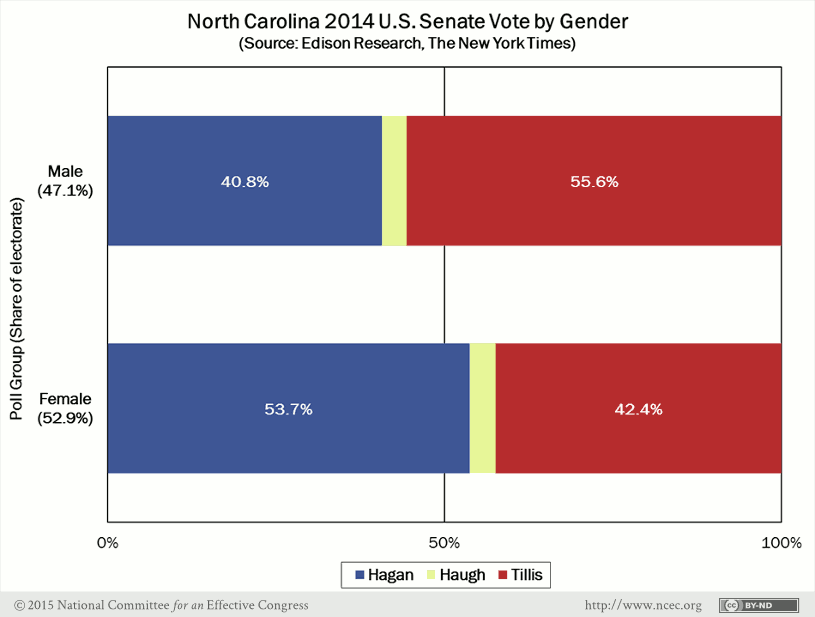

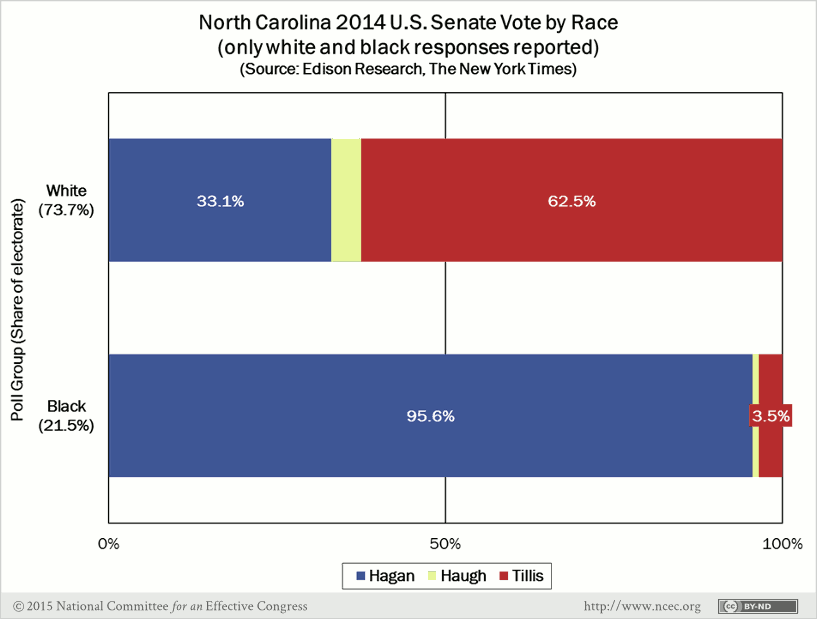

Race and Gender

Despite garnering 96 percent of the African-American vote, African-Americans comprised only 22 percent of the vote in North Carolina while whites accounted for 74 percent of the vote. Hagan’s loss is due, in part, to her poor performance among white voters, from whom she earned only 33 percent. Hagan lost by 18 points with white women, who had helped support her in 2008, and by a whopping 42 points with white men. In fact, this was a loss of 10 percent of white male support when compared to her victory in 2008. In 2014, Hagan suffered a 6 percent loss of male support and a 1 percent loss of female support. She only won 41 percent of the male vote and gained a slight edge over Tillis with 54 percent of the female vote.

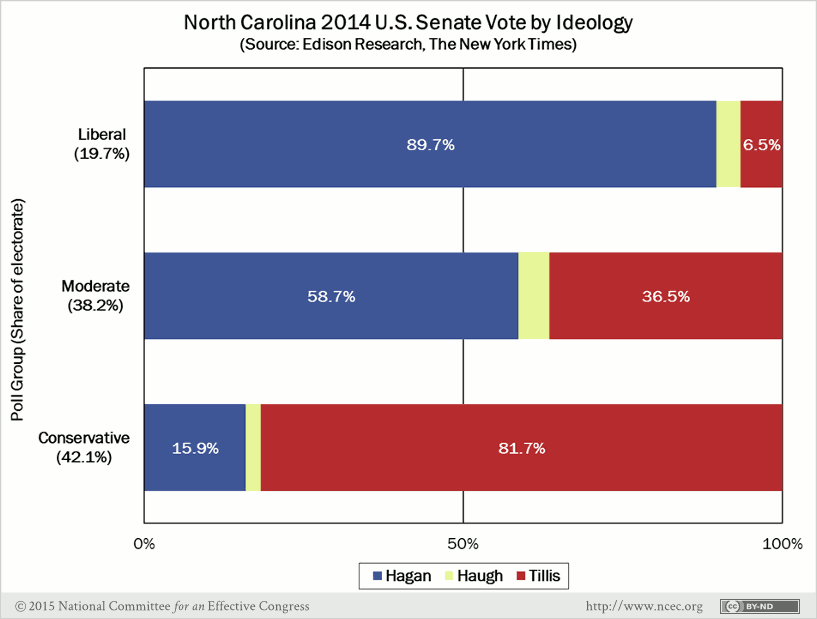

Ideology

Ideology played a larger role in Hagan’s defeat. In 2008, she won by 30 percent among moderates, who made up 43 percent of the electorate at that time; however, the moderate population fell to 38 percent in 2014 and there was a 5 percent decrease in moderate support for Hagan in 2014. The Conservative population grew by 3 percent between 2008 and 2014, and their support for Hagan decreased by 3 percent over that same time. The decrease of a moderate base and the loss of moderate votes certainly contributed to Hagan’s defeat.

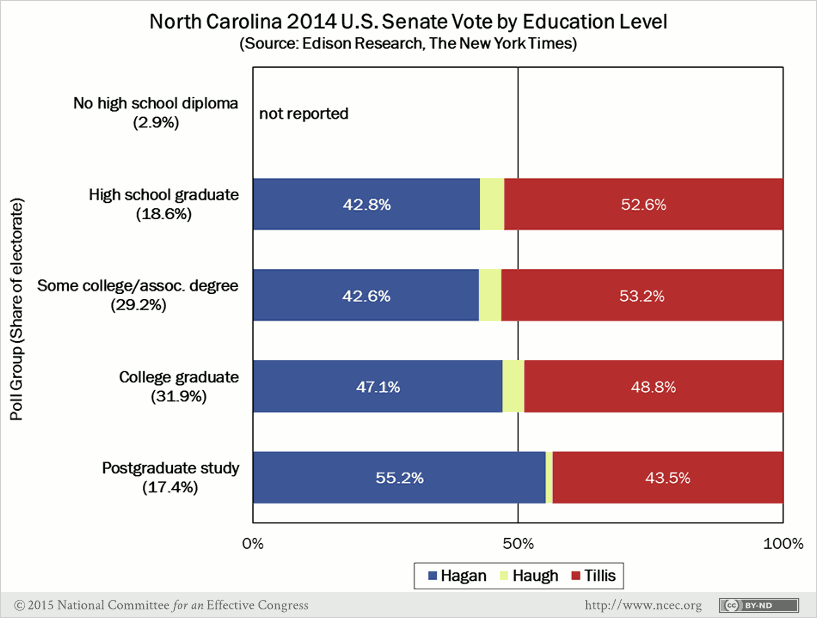

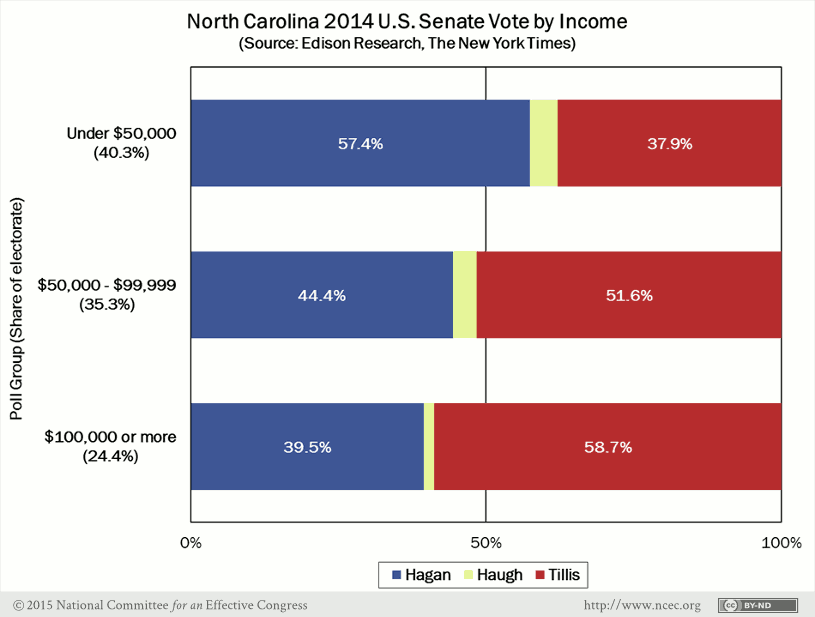

Education and Income

Hagan’s support also faltered along socio-economic lines; in 2008, she won by slight margins across all levels of education (between 2 and 6 percent). However, in 2014, she saw a loss in support at every level, with the biggest loss coming from voters who had only completed high school (a 9 percent decrease). The only bracket Hagan won was voters with a postgraduate education (55 percent to Tillis’ 43 percent), but even with this group, her performance was 4 percent lower than her previous election.

Across income brackets, Hagan maintained her base with individuals making less than $50,000 a year, only losing 1 percent of their support from 2008 to 2014; however, the population making less than $50,000 a year decreased by 9 percent between the two elections. In the growing middle class, making between $50,000 and $100,000 a year, Hagan struggled. She saw a 6 percent decrease in support among those voters, a bracket that she won 50 to 48 percent in 2008. Unsurprisingly, Hagan performed poorest among the wealthiest citizens (making over $100,000 a year), but she lost by a much wider margin in 2014 than in 2008 (19 percent versus 6 percent). This bracket also saw the largest population growth, a 5 percent increase, in the time between Hagan’s two elections.

Demographic Trends

While minority populations are growing in North Carolina, they are not growing fast enough to balance the influence of upper income white voters and partisan polarization on the whole. To reclaim general election viability, Democrats need to make stronger inroads with middle class voters, independents and moderate Republicans.

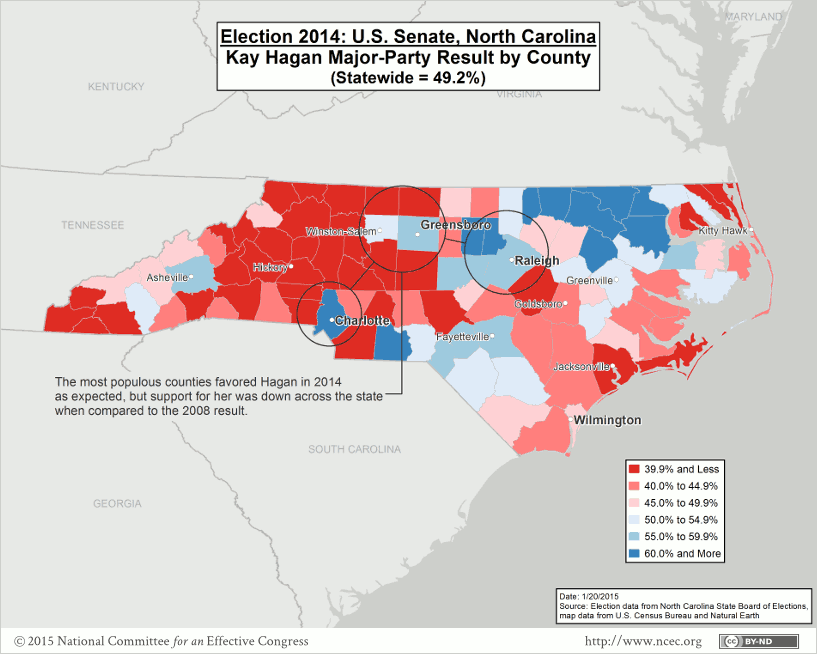

Geographic Overview

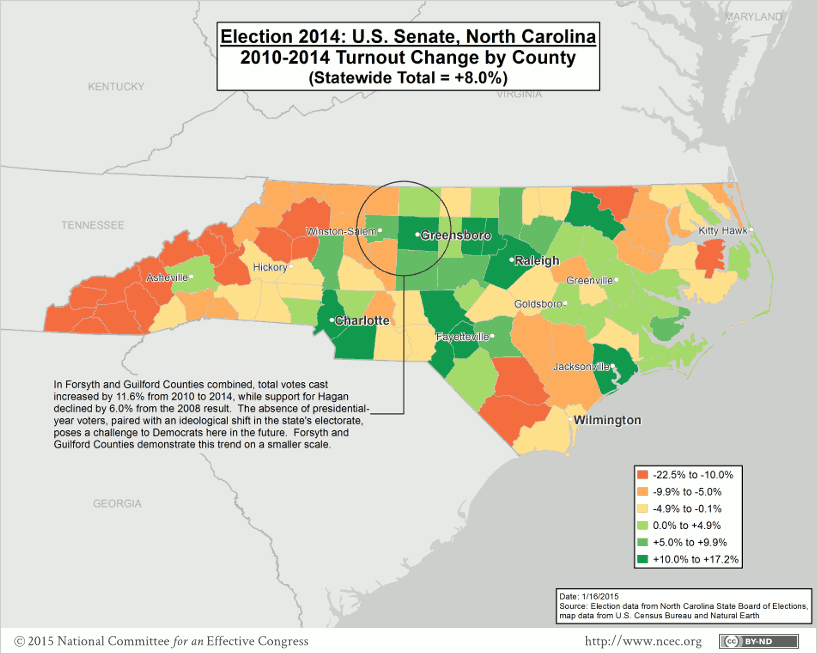

A look at the county level results reveals additional factors that contributed to Hagan’s loss. Mecklenburg, despite being the state’s most populous county, had fewer ballots cast than Wake, the second-most populous (9 percent versus 11 percent of the 2014 turnout). Hagan carried Mecklenburg with 61 percent of the vote and won Wake by a slightly smaller margin (57 percent of the vote). Both counties are urban and have consistently voted for Democrats—Hagan and Obama in 2008 and Democratic senatorial challenger Marshall in 2010. Interestingly, Mecklenburg voted for Republican incumbent Pat McCrory in the 2012 Gubernatorial election while Wake voted for Democrat Walter Dalton. In 2010, Mecklenburg made up more than 8 percent of the turnout, while Wake made up 10 percent; Hagan was helped by the slight increase in turnout between the two midterm elections.

Hagan won Guilford County with 57 percent and won Durham County with an overwhelming 78 percent. These results are unsurprising, as both are fairly urban counties with several colleges and universities each. In the 2014 race, Guilford County accounted for 6 percent of the total turnout and Durham County accounted for 3 percent; this is nearly the same as in 2010, when Guilford made up 5 percent and Durham 3 percent. The slight increase in Guilford’s turnout may be due to a larger college-educated population.

In Forsyth County (the fourth-largest by population), Hagan saw a 5 percent decrease in support from 2008 to 2014. The median household income for the county falls within the $50,000 to $100,000 bracket and Hagan suffered among voters in this socio-economic group. In 2014, Forsyth accounted for 4 percent of the total turnout, matching its share of the 2010 electorate.

In urban Buncombe County and exurban Cumberland County, Hagan saw success, winning 59 percent and 58 percent respectively. Buncombe in particular is a liberal pocket, as a UNC campus is located there in the more progressive city of Asheville. She only managed to split the vote in New Hanover County, garnering 78 fewer votes than Tillis. That comes as the result of a 6 percent decrease in support, which could be due in part to the county having a median income similar to Forsyth, but could also be due in part to New Hanover’s mostly white population, as Hagan lost support among white voters in 2014.

As demonstrated by Hagan’s performance in Carteret County (a low 31 percent), Tillis performed strongly in North Carolina’s rural counties. Carteret County, along with the other sparsely-populated, geographically large rural counties (such as Brunswick in the south) voted largely for Tillis. Interestingly, Libertarian Haugh gained some traction in the state’s western counties, garnering 8 percent of the vote in rural Swain and limiting the Hagan-Tillis race to percentages in the high 40s in other western counties. Hagan performed poorly with these rural counties in her 2008 election, and these counties helped McCain win North Carolina in 2012.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Hagan was never going to perform as well as she did in 2008 because of the outstanding circumstances surrounding the 2008 presidential election; the lower turnout in a midterm election was bound to hurt her in some way. Had Obama campaigned with her in North Carolina, there might have been stronger turnout among the Democratic and African-American voters that helped elect Hagan in 2008. Hagan’s narrow defeat demonstrates a wider problem within the Democratic party in 2014—not enough concentrated GOTV efforts among groups that had supported Hagan in the 2008, and a move away from Obama, despite the fact that a surprising amount of support for Obama in North Carolina in 2008 helped Hagan win her previous election.

Thom Tillis was endorsed by Jeb Bush and Mitt Romney and is viewed as a relatively moderate Republican. Additionally, his legislative experience and focus on business helped win over moderate and middle class voters who, in 2008, had supported Hagan. The midterm elections of 2010 and 2014 saw a voter turnout of 44 percent for both years. This was predictably lower than the presidential elections of 2012 and 2008, which saw voter turnout of 68 and 70 percent respectively. Hagan’s loss of moderate and middle class support, the failure to reach out to smaller, non-urban counties, and the predictably low turnout of a non-presidential year all contributed to her defeat.

Looking Forward

If turnout among traditionally liberal or Democratic voters is higher in 2016, and if the Democratic presidential candidate is able to make inroads with the more moderate voters in North Carolina, some narrow victories may be possible. However, given that North Carolina has two Republican senators, a Republican governor, and a largely Republican congressional delegation, it is hard to say that the state will be anything but conservative leaning in 2016.